Cleveland Mourns

Stephanie Tubbs-Jones

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Stephanie Tubbs Jones came to Congress nearly 10 years ago as a little-known Democrat from Cleveland who had to fill the big shoes of a near-legend, Louis Stokes.

But when news of her fatal brain aneurysm spread from Ohio to the nation's capital Wednesday, Tubbs Jones' reputation was well-established: tough, exuberant, passionate, partisan, a woman from modest means who rose to national prominence.

President Bush, whose policies Tubbs Jones criticized, said he was saddened by her death.

"Our nation is grateful for her service," he said, citing her work in "helping small businesses, improving local schools, expanding job opportunities for Ohioans, and ensuring that more of them have access to health care."

Hillary Rodham Clinton, whose presidential candidacy Tubbs Jones had embraced, and her husband, former President Bill Clinton, recalled Tubbs Jones as "one of a kind" and "unwavering, indefatigable."

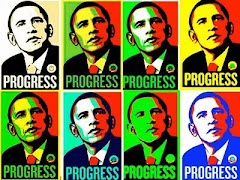

Barack Obama, whom Tubbs Jones had expected to see nominated next week as the first African-American presidential candidate of a major party, called her "an extraordinary American and an outstanding public servant."

"It wasn't enough for her just to break barriers in her own life," Obama said in a statement. "She was also determined to bring opportunity to all those who had been overlooked and left behind -- and in Stephanie, they had a fearless friend and unyielding advocate."

Tubbs Jones died at 6:12 p.m., after suffering a brain hemorrhage caused by a burst aneurysm.

"It is so stunning," said a shaken Dennis Kucinich, Tubbs' Jones congressional colleague from the other side of Cleveland. "She was so much a part of the community. It is hard to imagine."

The 58-year-old Democrat, the first African-American woman in Congress from Ohio, was in her Chrysler about 9 p.m. Tuesday when a Cleveland Heights police officer spotted her driving erratically. When the car stopped, the officer found Tubbs Jones unconscious but breathing. She was rushed to Huron Hospital in East Cleveland, where tearful local leaders arrived throughout Wednesday.

"She dedicated her life in public service to helping others and will continue to do so through organ donations," said a statement issued by her family, Huron Hospital and the Cleveland Clinic.

Gov. Ted Strickland, who served with Tubbs Jones in Congress, said he and his wife, Frances, are "heartbroken." He said Tubbs Jones "was a strong, courageous and compassionate advocate for the poor and vulnerable."

Tubbs Jones was admired by colleagues in both parties for her tenacity. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called her "a tireless force for justice, equality, and opportunity." Minority Leader John Boehner, a Republican from southwest Ohio, said she was "a passionate representative who worked tirelessly to make Cleveland a better place for her constituents."

Paired with an outgoing personality, her fearless approach took her from working-class Cleveland roots to Case Western Reserve University law school and rough-and-tumble Cuyahoga County politics before she arrived on the national scene.

She gained renewed prominence this year by campaigning passionately for Hillary Clinton's presidential bid. But just after the 2004 presidential election, she also drew national attention for her claims, made on the floor of the House of Representatives, that electoral fraud and manipulation led to Bush's re-election. It was only the second House election challenge since 1877.

That, more than any other single event, got her labeled as a partisan firebrand. Yet Steve LaTourette, the Republican congressman from Concord Township, said he considered Tubbs Jones "my dear, dear friend for more than 20 years, dating back to our days as county prosecutors."

"She was a force of nature and always the most popular and gregarious person in any room," LaTourette said.

Stokes, the 30-year congressman whose retirement created a chance for Tubbs Jones to run, described her as a "beautiful, bubbling, charismatic woman" who "was so highly talented." No matter where she went, he said, "she lit the room up."

Tubbs Jones, whose mother was a factory worker and father was a skycap at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, had planned to fly to Denver this Sunday for the Democratic National Convention. She was to be a super delegate and witness the formal nomination of Obama.

Obama, however, had not been Tubbs Jones' first choice. Before he secured the nomination, Tubbs Jones remained an advocate for Clinton, campaigning with her across the country. Tubbs Jones would not back down from critics, even the many in her district who preferred Obama.

"Her word had value to her," said the Rev. Jesse Jackson, a leading civil rights figure. "It didn't waver in the wind."

A

Cuyahoga County prosecutor and, before that, a municipal and common pleas court judge, Tubbs Jones was a seasoned politician by the time she ran for Congress in 1998. In the Democratic primary to pick a successor to Stokes, Tubbs Jones took on four opponents, including the Rev. Marvin McMickle and then-State Sen. Jeffrey Johnson.

Local pundits expected a splintered race. Instead, a confident Tubbs Jones won a stunning 51 percent of the vote in the 11th Congressional District, which includes the eastern half of Cleveland and several eastern suburbs.

She came to Congress with a school girl's enthusiasm rather than an old pol's attitude. Her taste for red dresses -- the color of her Delta Sigma Theta sorority -- and her 5-foot-9 stature made her stand out. At a black-tie social event early in her first year, she spotted U.S. Rep. Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin, the first openly gay woman in Congress and someone whose courage Tubbs Jones admired. The freshman from Ohio made a bee-line across the room to meet her, and the two became friends.

Tubbs Jones' congressional life centered on her membership on the House Ways and Means Committee, which deals with taxes and trade, and on issues such as medical and dental care for low-income children. After the 2006 election, Pelosi picked Tubbs Jones to chair the House Ethics Committee. The committee remains a target for those who say it is too soft on members of Congress, but Tubbs Jones beefed up staffing and started more ethics training programs.

She was active in the Congressional Black Caucus, and said she viewed herself as a voice for minorities across the United States. She pushed for bans on predatory loans, and for more federal money to research uterine fibroids, which are benign tumors that can result in unnecessary hysterectomies. Black women are at higher risk for fibroids.

She was one of the most frequent travelers in Congress, taking free trips to Caribbean resorts to speak at forums on minority business development. She was unapologetic for the travel, however, saying that trips to the Caribbean basin "connect leadership of the Caribbean with African-American members of Congress, just as the Jewish members of Congress are connected with Israel."

Tubbs Jones had an unusual share of tragedy in recent years. During her time in Congress, nine close relatives and in-laws, including her sister, parents and husband of 27 years, Mervyn Jones Sr., died. She coped with the tragedy by spending time on hobbies -- southern cooking and sailing -- and throwing herself into her work.

Tubbs Jones is survived by a son, Mervyn II, and a sister, Barbara Walker. Tubbs Jones' congressional spokeswoman, Nicole Williams, said funeral arrangements will be forthcoming.

Plain Dealer reporters Joe Wagner, Damian Guevara and Mark Naymik contributed to this report.

Stephanie Tubbs-Jones...

Always In Our Hearts